From The Station Eleven Vaults

On The Haunting Beauty of Lighting Tests

The subhead alludes to it, but I’ll say it directly, here: as a person who went from audience normie (someone who had never been on a set) to a showrunner, in his late-thirties, I notice certain things about production that I sometimes think are rote, to the people who’ve done it all their lives. “Production” is a state of being, in and of itself, and not necessarily happening where the cameras are; when you’re in the center of it, or, as Arthur Leander says in Episode 8 of Station Eleven, you are “in the shit” — it becomes the only thing that’s real. The rest of the world is an idea someone maybe pitched, one time, but it never got made.

Through the flux and flow of information and ideas, you can often meet people through their art, before you see them, or know their names. A pitch can be a first impression. Humans that you come to know well, and often become closer than family, for a time, present themselves to you in abstract form— attempts to make some tiny whisper in the script’s subtext into something real— to ask the central question of prep: Is this the thing? If not, lmk, and I’ll provide you with fifteen alts.

Mockups, storyboards, squiggled sketches on Zoom whiteboards, crumpled up sides with notes scribbled on them, DOODs, call sheets neatly folded, with the words, “Fuck everything” written neatly in the upper-right-hand corner— all of these are the ingredients of tv-making. Mostly, you’re so exhausted that it’s trash, but there are moments— and again, I can’t emphasize enough this feeling of rawness, and being opened up, 100% of the time you’re interacting with these micro-artifacts— when you realize that these things are the beautiful things. The show is just the outcome. “Production” is the living, vibrating cloud of human beings imagining the same thing together, slowly hearing the exact same story in their minds, at once.

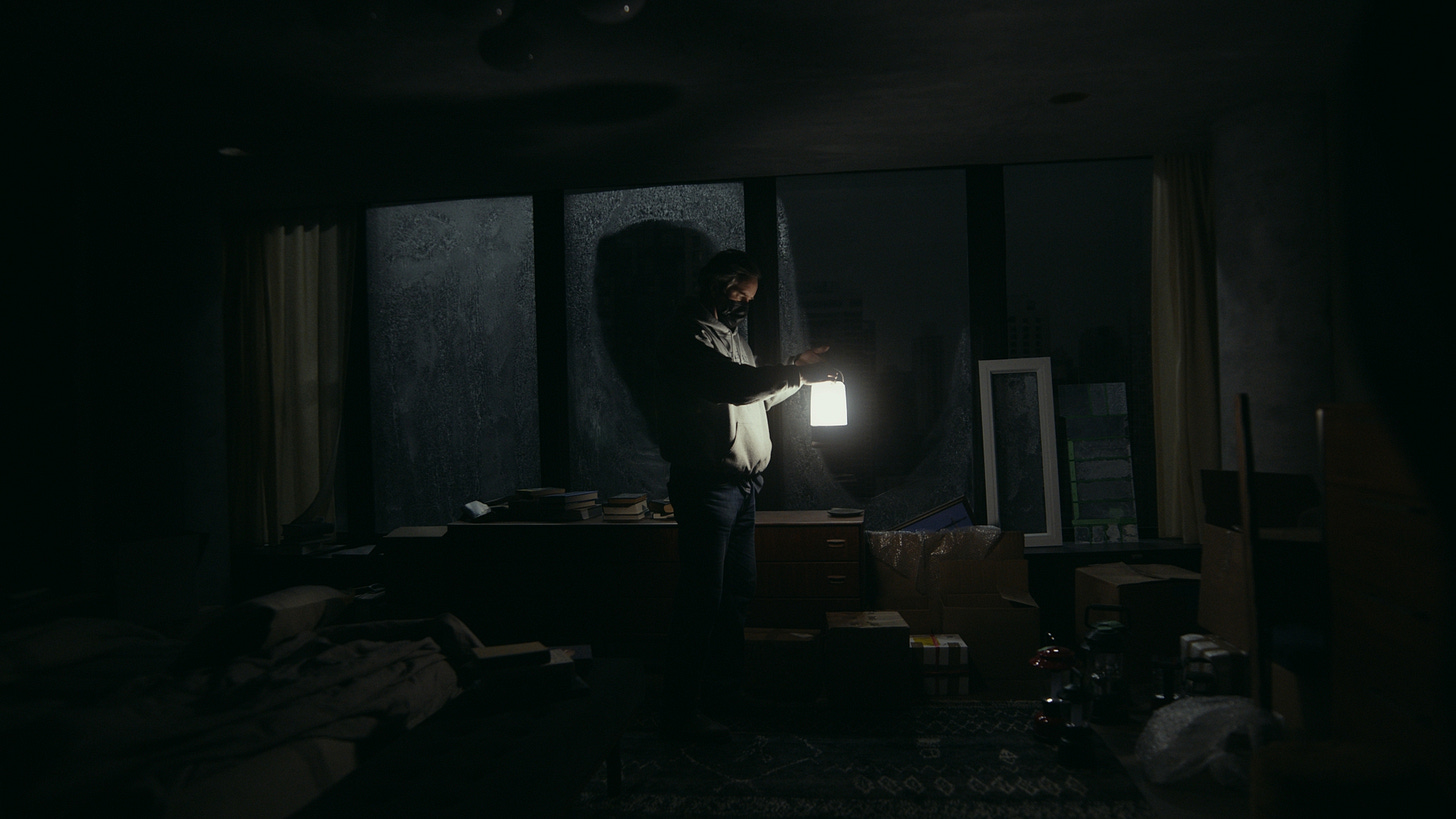

Maybe one of my favorite pieces of media left behind is the lighting test.

(I won’t go on and on to frame this, because really I just wanted to share these photographs, but finding them did get me thinking of all the hidden chambers of our industry, and how fascinating they are. I turned into a grownup in these spaces; I learned my lessons about people—every kind of ‘em— here. I think the subject of what it actually feels like to be doing this for 50, or 100 ,or 150 days in a row is a point of disconnect between creatives and executives in our industry. I have no idea how to describe it, and also feel a strange obligation to not describe it, coming from somewhere I don’t understand. We (literally anyone who is a part of the production) are in the midst of an interdimensional Zoom, when we are talking to someone who isn’t a part of the production. When I meet with the studio during the shoot, I don’t think anyone at the studio really knows— or maybe just knows what to do with— the fact that I am basically Bud from The Abyss, typing out my answers on my little writst pad, with pink water in my lungs, giving a thumbs up as I sink into the nothing. Call time’s 6:00 AM.)

The lighting test is simply that; the DP and the gaffer and the production designer and the director and her team’s chance to study the surfaces and physics of a space, alone and before anyone else is there to speak some other language. But the photos are always fucking beautiful, is what I’m saying! It’s ridiculous what can be laden with emotion. Do you know why? Because your DP is the best photographer you have ever met in real life. Always. You get reminded of this even in the “boring email” portion of making shows. The most boring AF meetings are like going to a museum. If you’re doing it right, the head of each department in your prodution is an artist, before anything else, and work with fierce pride; in this way, great HODs remain uncompromised. Every deck is a hyperdesigned masterpiece of clarity. Every test is not a test. The light test is where the gaffer is the showrunner, because there’s no way the showrunner understands what the fuck the gaffer’s thinking about. The showrunner just trusts you. He trusts you most when he can see your shared obsession.

For context: the Chicago portion of Station Eleven’s shoot was not supposed to be “the Chicago portion”; when we shut down in February of 2020, it was still not clear that the pandemic was going to put us all on ice for as long as it did. We were optimistic we’d be able to follow through with our original plan, which was to drop back into prep to prepare for Year Twenty, and shoot the wagons and the troupe, and their story, in the coming spring, in the woods around Lake Michigan, outside of Chicago.

Instead, what happened, happened. The decision to move the show is a different story, but we decided to move to Toronto, and almost a full year passed before we were shooting again. Here’s the incredible timeline of that apartment, where Frank, Jeevan, and Kirsten spend those holy days: on a scout in October of 2019, we decide Lakepoint Tower is where we want Frank’s apartment to be.

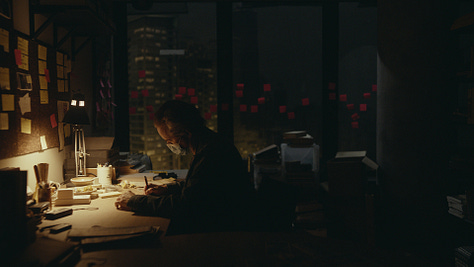

By January of 2020, we have permission to shoot outside and on the first floor of Lakepoint, but instead of using an apartment, our production design team, led by Ruth Ammon, builds a complete apartment as a set, knowing we plan to use it for an entire episode, later in the show; on one of our last days in Chicago, Hiro shoots Jeevan and Kirsten arriving at the apartment, for the ending of 101. Before that day’s shoot, though, I’m standing in the apartment, trying to figure out where the post-its should go on the wall. Why? The night before, Kim Steele and I have written a new draft of 107, and we’ve come up with the idea of using post-its to track Frank’s mental decline. But to be clear: I am guessing what we’re going to do, months into the future, as a later-ish point in a story I don’t know yet will ever happen. We are actively, in that moment, working on the details of Frank’s life, up to when Jeevan shows up with Kirsten. I remember telling someone to take a box-shaped amount of books out of the bookshelf that could create an eyeline for Frank to the window, knowing he would have a scene in which he saw Kirsten through it. MAYBE. I see Nabhaan Rizwan and talk about going to see the White Sox in the summer.

Then the world stops.

Sometime in May or June, in a very quiet and different world, a team of four people wearing masks enters our locked stages and begins to take apart the apartment that we’ve built. It needs to be deconstructed, packed up, and trucked to Toronto, where it will be rebuilt again there. We’ve made a replica of a real apartment, ten miles away, then taken it apart, trucked it several hundred miles to another country, and put it back together there. Time passed in the world, but it was as though that apartment, already before the shoot, existed outside of time.

Later, after these photos were taken, I had to stop and take a minute, walking onto the set. I was wearing my mask and surrounded by a new crew I didn’t know; the world had changed, but the place I was in… had not. It was the same. And there was Nabhaan, sitting with Himesh and Mackenzie. (I asked Nabhaan how he felt about the Blue Jays.) The first shot of Day 1 in Canada was going to be a single on Matilda as she watched the plane go down, only this time lit by candle. It was a direct pickup in the show’s timeline, but shot again, for a different visual idea: the flashback to the Y20 stage, and the strobing between timelines we had planned for 102. On the timeline of the show, we were backing up twenty second; here on the stage, it was 350 days later. Our connections seemed to reattach, though, like no time had passed. Matilda was two inches taller. The emotional language of Station Eleven was not something designed on a piece of paper, not something that was planned. The emotional language of Station Eleven was simply what it felt like to be making Station Eleven.

That’s what it felt like.

There’s a line in 108, when Kirsten is talking to Tyler, when she’s describing what it was like to have the graphic novel with her, amidst catastrophe. It didn’t matter that the world ended, to her, right then, because Station Eleven was the world. Ruth’s made-up apartment, this fake place, was the same place it had always been. That apartment made my heart turn back on. And in the next few weeks, I would be right there as Jeremy Podeswa, Lucy Tzerniak, members of our old crew, members of our new crew, and a few actors— Mackenzie, Himesh, Nabhaan, and Matilda— turned the show’s heart back on. Right in the same place it had gone into its regenerostasis

The first flicker of this wild and electrifying feeling came when our new DPs, Steve Cosens and Daniel Grant, did some lighting tests of the rebuilt apartment, and emailed them to me while I was still trapped in quarantine, in a Toronto hotel. Lighting photos are incredible, because they’re populated by different people from the crew, as well as stand-ins. I didn’t know who any of these people were, and it hadn’t been quite so frosty the last time I’d seen the apartment, but I knew this place. I’d imagined it and inside of it. People I’d imagined had fought to save their souls inside of it, and now it had become real again. I was in Toronto, but sure as shit that was Chicago. A broken and powerless one, but the one we had imagined. It was, despite everything, still real.

These photos were how I met Daniel, our new DP. Now I knew him; by “knew him” I mean I knew his vision for the show. These are photos testing lights, but they’re also ideas. Maybe we do this for Frank’s POV when Jeevan’s watching the news, the night of the apocalypse? But maybe then this in 107, when Jeevan’s waking up, while Frank’s talking about the mine. How’s this for Kirsten, looking at the sunrise? Maybe this, when Frank tells Kirsten his favorite character is “all of ‘em”, and Y20 Kirsten hovers by the bookshelf, listening.

If you look closely, maybe you’ll also see few photos capturing the mad idea of a showrunner, standing alone on stage with a bunch of post-its, trying to think out what kind of zig-zag situation best reads “slowly losing his mind”, not quite aware that the answer is: exactly what he’s doing right now.

He’s a ghost, though. That wasn’t now. This is Toronto. That ghost is standing in Chicago, in this not-apartment, doing that a year ago. He hasn’t yet gone to Lowe’s, one night, and wandered through the aisles, looking for a generator, worried what the fuck was going to happen, then spent six months pressed into a dense ball of matter and identity, once known as family, locked together in a space, forfuckingever. Dude knew to do the stickers, back then, but he hadn’t learned how to really tell the story. That was still coming. We were all about to be dragged through the reality of is this the thing? The “now” I had to learn about was coming in the future. Toronto Me realized it was the same thing all these strangers, standing in Frank’s home, had just gone through, too. We felt the same.

Then we shot it.

I loved Station Eleven (thank you thank you) and I wish so many more people had watched it—these photos truly bring me back to watching it for the first time and being rapt and heartbroken both. Astonishing art.

"The show is just the outcome. “Production” is the living, vibrating cloud of human beings imagining the same thing together, slowly hearing the exact same story in their minds, at once."

This is fascinating. I hope to experience this someday.

I think superfans probably pick up on some of this when we vibe with a show. Admittedly, it's likely 10% of whatever was happening, but some shows you just feel it.

Are there studio execs that are also fans of the work being done on a production level and champion it internally as it's ongoing? Or does that not really happen?